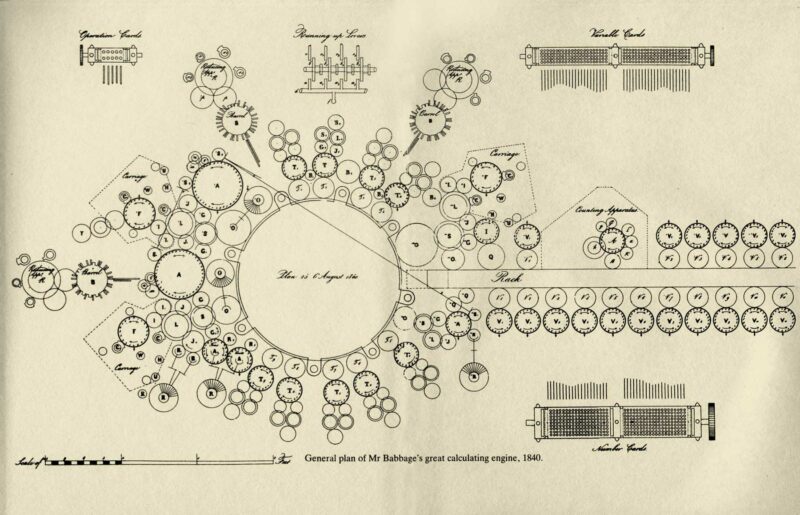

The Analytical Engine was a proposed mechanical general-purpose computer.

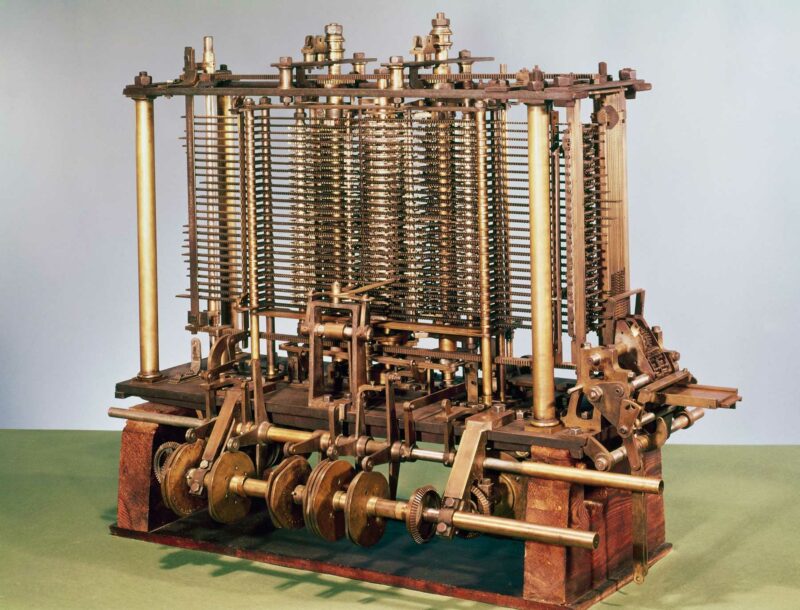

The Analytical Engine was a steam-driven mechanical computer with approx. 28,000 parts, 30 x 10 m in size. Its memory was approximately 20.7 KB.

Goal of this fantastic machine was the resolution and automation of the mathematical processes known at the time by transferring them to the basic arithmetic operations.

The Engine was controlled with punch cards and a programming language with loops and conditional branching. The output of results was visualized via printer, curve plotter, punch cards or metal plates.

Due to constant changes and improvements, only individual parts were built. The engine’s finalized mode of operation would presumably work correctly. The Engine is today being (re)constructed as part of the Plan 28 project.

Copying nautical or logarithmic tables is tedious work and even more prone to errors. The English mathematician Charles Babbage therefore suggested to the British Admiralty to build a machine for this purpose. Inspired by the new mechanical looms and by the development of automata in the emerging watchmaking industry. He combined rollers and cams in order to apply mathematical operations, which always remained the same, to different initial values with constant precision. He thus created the first, still purely mechanical calculators in the 19th century. They are the precursors of today’s computers. Ada Lovelace developed the programs to run these machines. s are created that can also reproduce irregular movements as well as forward and backward movements. Babbage clocks are, in a sense, ‘non-linear’ clocks. Their microprocessors open up elements of complex rules (algorithms) to modern haute horlogerie, that we know otherwise from computers.