Prof. Dr. med. Albert Bühlmann, University of Zürich

Published 1961 by J.R.Geigy S.A Switzerland «Der Weg in die Tiefe» in five bulletins

Report on the diving experiment in Toulon on the 4th of November, 1960

The effects of the increasing overpressure on the organism with increasing water depth can all be studied in overpressure chambers, which offers great advantages because of the direct observation possibilities and the elimination of all difficulties connected with the water itself, such as thermal insulation, visibility, etc. Thus, hyperbaric chambers were built and used already in the last century. They even enjoyed a certain popularity in medical practice for «air and oxygen baths», in that one wanted to promote better diffusion into the tissue with the oxygen pressure, which was, however, only slightly increased.

A 10 meters water column corresponds to a pressure of 1 atm. If the pressure in a chamber is increased to 10 atm by means of compressed air, for example, the same conditions result as at a diving depth of 100 m.

In 1959, prior to our larger diving tests, we carried out some investigations in a small, mobile hyperbaric chamber, which allows a maximum pressure of 8 atm, i.e. a diving depth of 80 m. The results were to be of great importance for further development. Such small, easily transportable hyperbaric chambers should be available as rescue equipment in case of decompression accidents for all major diving experiments and ship salvages. We ourselves have not made a single deep dive attempt without a hyperbaric chamber provided. In case of a too rapid ascent with the danger of a decompression accident it would always have been possible to recompress the diver within a few minutes in the chamber.

In the design and construction of a hyperbaric chamber, great care must be taken to ensure maximum safety in terms of wall thickness, quality of materials and welds, sealing of doors and windows, etc. If the chamber were to burst, very large energies, comparable to many kilograms of dynamite, would be released and lead to the destruction of the house. Chambers that allow an overpressure of more than 20 atm, i.e., diving depths of more than 200 meters, have therefore been built only in exceptional cases. In the United States, there is a hyperbaric chamber with a maximum pressure of 25 atm.

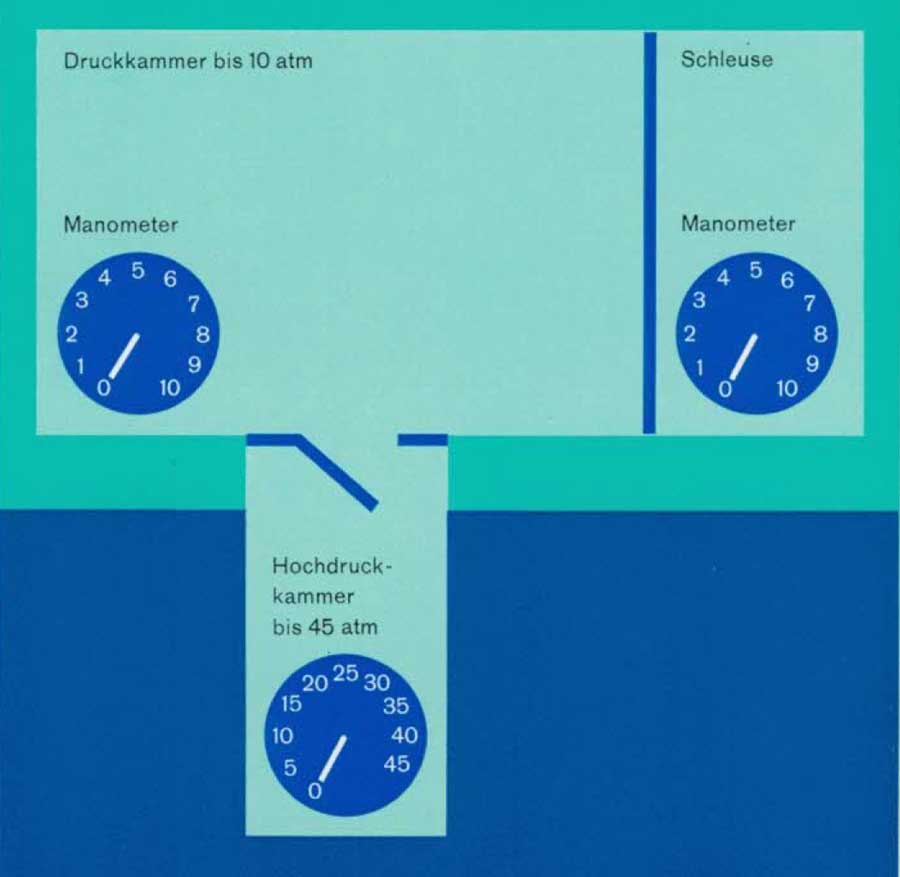

The famous French diver and oceanographer Cousteau constructed a hyperbaric chamber for the French Navy (Fig.1 and 2), which allows a pressure of 45 atm in the downwardly attached high-pressure part, which can also be filled with water, and thus the imitation of a diving depth of 450 m.

This apparatus of considerable dimensions is of great importance. This equipment of considerable dimensions is installed in the arsenal of Toulon and serves a special troop of the Navy, the GERS (Groupe des études et des recherches sous-marines) for training purposes and research. So far, however, they have only gone to full pressure in blind tests; no tests have yet been conducted with trapped divers at pressures greater than 10 atm, or 100 meters diving depth.

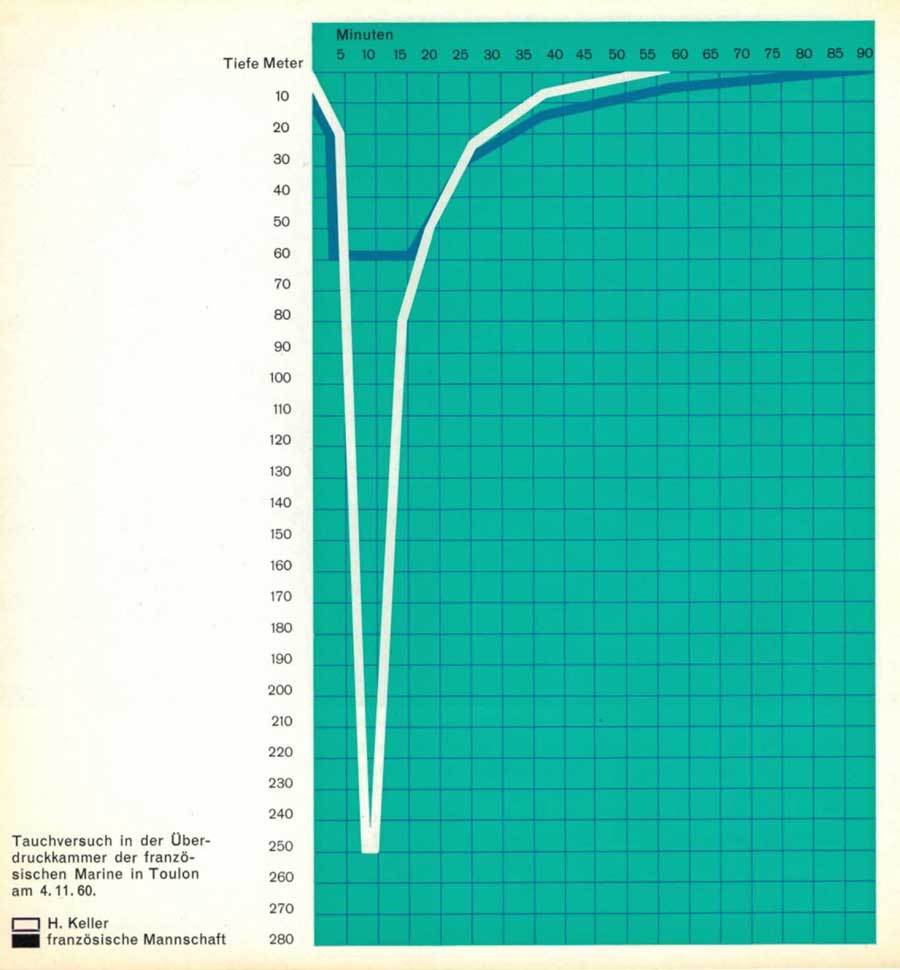

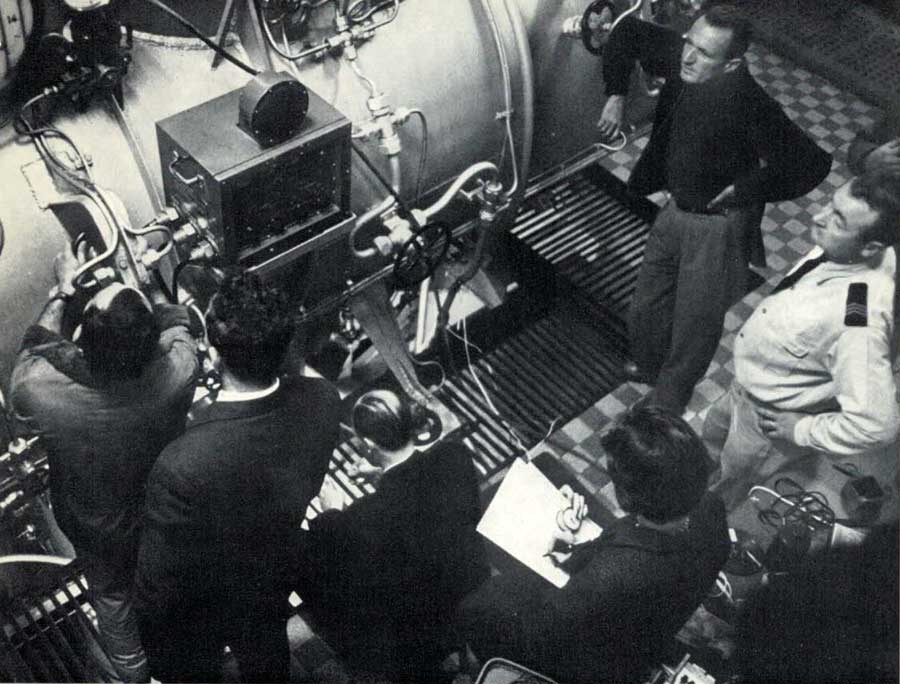

Thanks to Cousteau’s efforts, this overpressure chamber, which is unique in the world in terms of performance, was made available to us for a deep dive test at our own risk. Our aim was to demonstrate that with suitable methods it is not only possible to dive much deeper than before, but that it is also possible to return to normal pressure relatively quickly, which (as will be explained in a later bulletin) has great practical significance. After we had tested the whole previously precisely calculated program once in a blind test without divers, but with all the equipment, the real test was carried out on November 4, 1960, in the morning, in the presence of numerous military and civilian experts. Keller was in the high-pressure section, which was submerged, in full diving gear with the breathing apparatus. Communication with the outside was by direct sight and by telephone. The control of breathing was made possible in the simplest way with a throat microphone. The time sequence can be seen in the following diagram.

The rise in pressure was remarkably rapid. From 0 to 25 atm, barely 10 minutes were required. The French crew in the upper chamber went along only to 6 atm, or 60 meters diving depth. When the pressure in the high-pressure section was increased from 15 to 25 atm, the large room was very quiet. Everyone knew that Keller was now in a pressure zone where no one had been before. Will it be all right?

By means of voice communication, I was able to keep myself constantly informed about Keller’s condition and, if necessary, interrupt the experiment.

An intercom system allows contact with the divers.

The general tension gave way when the 25 atm were reached and the pressure was reduced again. «ça marche bien, mon commandant.» Our guests and staff breathed a sigh of relief. We ourselves were convinced of the correctness of our method and saw no particular risk at all. To the French, however, especially to the diving experts, the attempt must have seemed extremely daring.

«What kind of gas does Keller use to fly into the sky?»

was their joking yet concerned question. They had been working with this hyperbaric chamber almost daily for years and had never gone deeper than about 100 meters. They were aware of all the difficulties of deep diving and understandably had trouble believing that a couple of landlubbers from Zurich seemed to be able to do more than they could.

We are all the more indebted to our French colleagues and the military authorities for their cooperation; even though the test was carried out at our own risk, an accident would have burdened and inconvenienced them. For the real diving experts, it was only now that things became really interesting. What happens during decompression?

According to the methods used so far, a serious decompression accident would certainly have to occur if we kept to our time program. Also in this phase I could only explain again and again reassuringly that everything goes well and according to our program. After about 8 1/2 minutes, the pressure in the high-pressure section had already been reduced to 6 atm again, so that the door to the large chamber with the French crew could be opened. Keller climbed into the upper chamber, where the pressure was then reduced to 2 atm within 6 minutes. He now went into the airlock, where he completed decompression to normal pressure within 30 minutes. Then the door was opened and the Winterthur diver left the chamber beaming to receive the congratulations of the spectators.

The French team needed about another 30 minutes for decompression. This difference, sensational for the experts, on the one hand a diving depth of 250 meters compared to only 60 meters and nevertheless a decompression time shorter by half an hour, was not at all intended on our part, but resulted by itself, because diving was done in parallel with the classical method and our new procedure.

Our demonstration was a complete success: it had become clear to the experts that a new era in diving technology had begun.